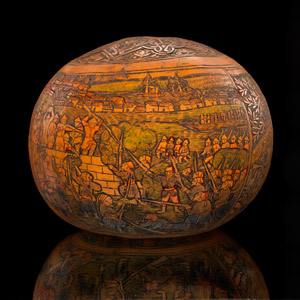

Mariano Flores Kananga (Quechua, ca. 1850–1949), carved gourd

ca. 1925

Ayacucho, Peru

Gourd, pigment

17 x 18 cm

Egbert P. Lott Collection

15/9952

We are confident that this engraved gourd—an Ayacucho-style sugar bowl—was crafted by Mariano Flores Kananga, a Quechua-speaking peasant from the village of San Mateo, at the top of Mayocc in Tayacaja Province, Peru. Flores is recognized as the best narrator of Peruvian customs, stories, and important events working in the medium, a traditional art of his time. In pieces made by Flores, we see information in even the smallest detail, so much so that people recognized each figure he depicted. This scene—the final encounter between Peruvian and Chilean forces at Arica on June 7, 1880—represents one of the culminating moments of the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), which weakened Peru’s position as a continental power.

Flores’s narrative blends maritime and Andean landscapes. From a wall or fort, Peruvian fighters—some shown wearing lapichuco, conical headgear typical of the Andean regions of Ayacucho and Andahuaylas—throw stones, mud bricks, and sticks at Chilean infantrymen, many of whom are dressed in the Zouave style adopted from the French army. The Peruvians are defending a mountain village, represented by a central plaza, churches, adobe houses with gabled roofs, and surrounding fields. Turning the gourd, we see the port of Arica, where the Chilean army surrounds the Peruvians, blocking their escape. The Chilean ships Cochrane and Blanco Encalada are shown in the background. In the final scene, on the hilltop where the battle ended, Colonel Francisco Bolognesi lies dying, aiming his revolver at his attackers, in fulfillment of his promise to fight until the last shots are fired. Another colonel, Roque Sáenz Peña, is being captured, while Commander Guillermo More falls lifeless at the feet of his brothers in arms. Peruvian sailors, survivors of the naval battle of Angamos, are shown trying to hold off the enemy with bayonets.

The understanding of property, citizenship, and civil rights among Quechua and Aymara-speaking Peruvians was worlds apart from the republican and constitutional ideas forced on them through conquest and colonialism. Indigenous Peruvians identified national government with Peru’s ethnic tax. When the Chilean expeditionary army entered the highlands, however, indigenous Peruvians fought to maintain their dignity and way of life on lands the Quechua had inhabited for millennia. The Peruvian coat of arms that decorates the last scene of the Battle of Arica is a symbol of the people’s love for their homeland.

Mariano Flores, who was nearly a century old when he died in 1949, would have been around thirty during the war. The details of his re-creation lead us to believe that he may have reproduced from memory an event he witnessed, perhaps even one in which he took part. Vivid stories might have provoked in his imagination and hands the capture of the hill and the failed naval campaign. But what are we to think about those Zouave-uniformed Chileans, whose appearance he is unlikely to have learned from books to which he could not have had access? Or the unusual headgear worn by the guerilla defenders of their country, about which the official history still has not given any account? Here ancestral art and vision are fused with personal and national history to create one of the most unique portrayals of war ever made, and to commemorate a moment of indigenous Peruvian patriotism still relatively unknown.

—Fernando Flores-Zuñiga, Instituto Riva Aguero de la Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru; Percy Medina (Quechua); and Elizabeth Chanco (Quechua)

Mariano Flores Kananga (Quechua, ca. 1850–1949), carved gourd, ca. 1925. Ayacucho, Peru. Gourd, pigment; 17 x 18 cm. Egbert P. Lott Collection. 15/9952

+

Mariano Flores Kananga (Quechua, ca. 1850–1949), carved gourd, ca. 1925. Ayacucho, Peru. Gourd, pigment; 17 x 18 cm. Egbert P. Lott Collection. 15/9952

+