Images of Plains and Plateau tribes have been shaped largely by the bitter “Indian Wars” of the latter half of the 19th century, when many Native communities fought U.S. efforts to extinguish Indian control of tribal lands. Accounts of this conflict dominated the nation’s newspapers and illustrated magazines at the beginning of the media age, to the extent that, for many people, the Plains warrior remains the iconic American Indian.

The Indians of the Plains and Plateau have always valued courage in war. During the second half of the 19th century, the Omaha Dance, which honors the deeds of warriors, spread from the Omaha Nation to other tribes on the Plains. These societies, however, have also always been linked by social, cultural, diplomatic, and trade relations. Living on a vast prairie that supported huge herds of buffalo, elk, and deer, these peoples paid homage to the Creator and to the natural world that sustained their lives.

Several of the objects highlighted here are associated with Plains and Plateau leaders who fought to defend their nations in the 1870s and 1880s. Yet the museum’s collections from the same time and place also include a beautifully beaded cradleboard, a deer-hide dress decorated with cowrie shells, and the fashionable Victorian wedding ensemble worn by Inshata–Theumba (Susette La Flesche), an activist who campaigned for Indian citizenship and land rights. As these objects and their histories illustrate, clearly there were many ways of being Indian in the 19th-century American West, and they involved great creativity and resilience.

Apsáalooke warrior’s exploit robe

+

Wedding dress worn by Inshata-Theumba (Susette La Flesche or Bright Eyes, Omaha, 1854–1903)

+

Moccasins associated with Peo Peo T’olikt (Bird Alighting, Nimi’ipuu (Nez Perce) b.?–1935)

+

Skidi Pawnee rattle

+

Peyote Rattle made by Nishkuntu (John Wilson or Moonhead, Caddo/Delaware ca. 1845–1901)

+

Shirt associated with Tashunca-uitco (Crazy Horse, Oglala Lakota, 1849–1877)

+

Lakota square hand drum

+

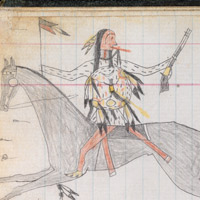

Sunka Luta (Red Dog, Oglala Lakota, ca. 1848–d.?), ledger book drawings

+

Tomahawk associated with Mee-nah-tsee-us (White Swan, Apsáalooke (Crow) ca. 1851–1904)

+

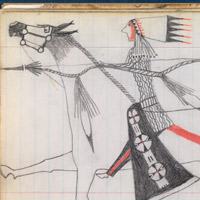

High Bull (Northern Cheyenne, ca. 1848–1876), Double trophy roster book drawings

+

Walla Walla pouch

+

Shirt associated with Sinte Gleska (Spotted Tail, Sicangu Lakota, 1823–1881)

+

Walla Walla dress

+

Nimi’ipuu (Nez Perce) quiver

+

Kootenai baby carrier

+

Ponca(?) parfleche bag

+

Comanche leggings

+

Iowa drop

+

Comanche peyote fan

+

Arapaho pipe bag

+

Iromagaja (Rain in the Face, Hunkpapa Lakota, ca. 1835–1905), drawing

+

Piikani Blackfeet (Northern Piegan) mirror board and pouch

+

Shield associated with Chief Arapoosh (Sore Belly, Apsáalooke [Crow], ca. 1795–1834)

+

Tsuu T’ina (Sarcee) coat

+

Tsuu T’ina (Sarcee) padded saddle

+

Assiniboine (Stoney) rifle case

+

Sahnish (Arikara) baby carrier

+During the 1930s, a terrible drought parched the Plains. In North Dakota, members of the Hidatsa Water Buster Clan asked Heye to return a medicine bundle important in ceremonies to bring rain. Heye was initially reluctant to part with the bundle, which he acquired in 1927, twenty years after the son of the clan’s bundle-custodian sold it to a Presbyterian missionary. When the press and government officials showed interest in the clan’s request, Heye changed his mind.

In 1938, two Hidatsa elders, Drags Wolf and Foolish Bear, traveled east to collect the medicine bundle. Their first stop was Washington, D.C., where they met President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The next day, the Hidatsa attended a ceremony in New York, where they gave Heye a powder horn and war club in exchange for the medicine bundle.

In 1977, twenty years after Heye’s death, museum curators came upon a wooden box, stashed in a stairwell. Inside were items that belonged with the medicine bundle. It is unclear if the contents had become separated from the bundle or were deliberately set aside. The items were later returned to the Hidatsa. Click here to read more...