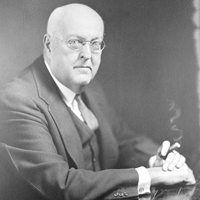

George Heye’s Legacy: An Unparalleled Collection

The objects in this exhibition were largely collected by George Gustav Heye (1874–1957), a New Yorker who quit Wall Street to indulge his passion for American Indian artifacts. Over time, Heye gathered some 800,000 pieces from throughout the Americas, the largest such collection ever compiled by one person.

Heye began collecting in Arizona in 1897. Afterwards he purchased large assemblages from museums and collectors, hired anthropologists to undertake collecting expeditions, and sponsored excavations at ancestral Native sites. Heye also traveled widely, buying as much as he could, whenever he could. In 1916, he established the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation, which opened to the public in upper Manhattan in 1922. According to the New York Times, the new museum was dedicated to “unveiling the mystery of the origin of the red men.…”

Heye died with no definitive answer to that “mystery.” But he left behind a singular collection, which was transferred in 1989 to the Smithsonian Institution, becoming part of the National Museum of the American Indian. Today, the objects in Heye’s collection are being reinterpreted by the descendants of the people who made them, providing American Indian perspectives on the Native past and present.

Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, and Gran Chaco

“The Museum expedition to Tierra del Fuego had for its primary purpose the formation of a collection representing the material culture of the [Selk´nam and Yámana] Indians before those tribes should become extinct.” So wrote Samuel K. Lothrop, an archaeologist who led expeditions for Heye’s Museum of the American Indian during the 1920s. Traveling to Native lands and communities at the southern tip of South America, Lothrop assembled and shipped to New York ceremonial masks, hunting and fishing equipment, tools, containers, horse equipment, and other items shown here.

Lothrop remembered Heye as “a strong-willed character who liked to do things in his own way,” including the occasional use of guesswork to identify objects. Consequently, Lothrop observed, information about the museum’s collections was sometimes inaccurately recorded—an issue the staff of the National Museum of the American Indian addresses today in consultation with Native peoples. Even so, Lothrop credited Heye with amassing an exceptional collection and for creating a museum to display it. When Heye died in 1957, Lothrop wrote, “His museum is his monument.”

The Andes

Heye’s passion for collecting objects representing ancient Andean civilizations dates to 1906, before most professional archaeologists identified Latin America as a focus for research. Heye’s interest in South American antiquities was influenced by Marshall H. Saville, a Columbia University archaeologist who developed a comprehensive, long-term research plan for building Heye’s collection. In 1907, Heye sent Saville on the first of several expeditions to ancestral Indian sites in Ecuador. The digs provided Heye with an important collection of Andean artifacts, including carved stone thrones once used by spiritual leaders.

By the time of his death in 1957, Heye had acquired hundreds of treasures from pre-Columbian cultures throughout Latin America. Particularly notable are examples of Valdivia pottery, the Western Hemisphere’s oldest-known ceramics.

The Amazon

George Heye’s collection includes feather headdresses and ornaments, hunting and fishing tools, dance outfits, masks, and ceramic figures made by the Native peoples of the Amazon. One of the individuals who helped to assemble the collection was the explorer, anthropologist, and writer Victor Wolfgang von Hagen. During his travels through Shuar territory in Ecuador, von Hagen attended tribal ceremonies, after which he traded knives and other items for objects, especially feather ornaments worn by men. After one ceremony, he boasted of having acquired “feather head-pieces of every kind of bird known to the Upper Amazon,” as well as “yards” of earrings, some made from the wing cases of “beautiful green-gold beetles.”

After spending six months among the Shuar, von Hagen concluded that their warlike reputation among non-Natives was largely undeserved. “Not once…did an occasion arise when our physical safety was in doubt,” he said. “Invariably we were treated with hospitality and courtesy, and the farther we left Christianity and civilization behind us, the more honest and friendly the Indian became.”

Mesoamerica and the Caribbean

Heye’s passion for collecting objects representing ancient Andean civilizations dates to 1906, before most professional archaeologists identified Latin America as a focus for research. Heye’s interest in South American antiquities was influenced by Marshall H. Saville, a Columbia University archaeologist who developed a comprehensive, long-term research plan for building Heye’s collection. In 1907, Heye sent Saville on the first of several expeditions to ancestral Indian sites in Ecuador. The digs provided Heye with an important collection of Andean artifacts, including carved stone thrones once used by spiritual leaders.

By the time of his death in 1957, Heye had acquired hundreds of treasures from pre-Columbian cultures throughout Latin America. Particularly notable are examples of Valdivia pottery, the Western Hemisphere’s oldest-known ceramics.

The Southwest

Heye’s interest in southwestern materials was supported by Harmon W. Hendricks, a copper-industry magnate and trustee of the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation. One of Hendricks’s biggest contributions was financing the excavation of Hawikku, an ancestral village in New Mexico, where the A:shiwi (Zuni) first made contact with Europeans. The dig, which employed 39 Zuni workmen, was conducted from 1917 through 1921 and in 1923, and uncovered approximately 25,000 artifacts as well as human remains. It was one of the most extensive archaeological excavations of a single site in the United States up to that time.

Objects excavated by the Hendricks–Hodge expedition illuminate life in A:shiwi villages before and after the arrival of the Spanish. These pieces provide unique insight into Native American history in the Southwest, and are of particular importance to the people of Zuni Pueblo. Since 2002, the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center at Zuni, New Mexico, has displayed objects from the Heye collection in a community-curated exhibition entitled, Hawikku: Echoes from Our Past. Among other issues, the exhibition recounts the arrival of anthropologists and ethnographers at Zuni Pueblo, as well as the excavation of Hawikku.

Plains and Plateau

During the 1930s, a terrible drought parched the Plains. In North Dakota, members of the Hidatsa Water Buster Clan asked Heye to return a medicine bundle important in ceremonies to bring rain. Heye was initially reluctant to part with the bundle, which he acquired in 1927, twenty years after the son of the clan’s bundle-custodian sold it to a Presbyterian missionary. When the press and government officials showed interest in the clan’s request, Heye changed his mind.

In 1938, two Hidatsa elders, Drags Wolf and Foolish Bear, traveled east to collect the medicine bundle. Their first stop was Washington, D.C., where they met President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The next day, the Hidatsa attended a ceremony in New York, where they gave Heye a powder horn and war club in exchange for the medicine bundle.

In 1977, twenty years after Heye’s death, museum curators came upon a wooden box, stored in a stairwell. Inside were items that belonged with the medicine bundle. It is unclear if the contents had become separated from the bundle or were deliberately set aside. The items were later returned to the Hidatsa.

The Woodlands

Several of the pieces shown here were assembled by Clarence Bloomfield Moore, an amateur archaeologist who excavated ancient Native sites in the Southeast from 1891 to 1918. When the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences sent Moore’s 35,000-piece collection to storage, Heye offered cash to bring the assemblage to New York and made an impassioned appeal. “I will do anything in the world to help along the transaction,” he told Moore. “I know positively this is the place for your magnificent collection, where it will be taken care of properly, will be of use to science, will not be neglected, and will be personally loved.”

When Heye’s people arrived to collect the objects, they encountered Harriet Wardle, the academy’s curator for archaeology. Irate that Heye had arranged to spirit the collection to New York without her knowledge, Wardle resigned immediately. Heye considered the acquisition a great personal coup, but Wardle never forgave him or his associates. As one of Heye’s successors recalled, Wardle “never met a member of the Heye Foundation without a glitter in her eye and a tightening of her lips.”

California and the Great Basin

One of Heye’s most intrepid collectors was Mark R. Harrington, a young archaeologist who traveled throughout the United States, Mexico, and Cuba, conducting archaeological digs, visiting tribal communities, and collecting objects between 1908 and 1928. Among Harrington’s triumphs was the excavation in 1924 of Lovelock Cave in western Nevada.

Long sealed by an earthquake, Lovelock Cave had been used for storage and shelter by Native peoples for several thousand years. Inside, Harrington uncovered extensive evidence of ancient Native life, including a cache of 2,000-year-old duck decoys, the world’s oldest. Fashioned from tule reeds and feathers, the decoys once lured waterfowl to hunters in the marshlands of ancient Lake Lahontan.

Harrington left Heye’s museum in 1928, but always spoke kindly of his former boss. “During all my twenty years in George Heye’s employ,” he recalled, “I found him a wonderful man to work for.” When Harrington’s son was born, he and his wife named the baby Johns Heye Harrington.

The Northwest Coast

Heye bought his first Northwest Coast object—a Tlingit shaman’s rattle—from a Los Angeles curio dealer in 1904. When he died in 1957, Heye had amassed some 27,000 objects from the Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest. Among them were a series of Kwakwaka´wakw ceremonial masks, rattles, and regalia confiscated in 1921 by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police following a potlatch at Village Island, British Columbia. These traditional gift-giving ceremonies were banned by Canadian authorities from 1884 until the law was repealed in 1951. During a 1922 collecting trip to Vancouver Island, Heye purchased 35 of the 450 confiscated items for $291. In 1926, he acquired an additional 11 objects from the wife of the Canadian Mountie who had assisted in prosecuting the participants of the 1921 potlatch.

The National Museum of the American Indian has since returned objects to the Kwakwaka´wakw, who formally requested the repatriation in 1985. These pieces are now part of the collections of the U'mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, and the Kwagiulth Museum and Cultural Centre in Cape Mudge, both in British Columbia.

The Arctic and Subarctic

Heye’s Arctic collection includes ceremonial masks made by the Yup´ik of western Alaska. The masks were worn during dances to please animal spirits and ensure success in hunting. Each mask was worn once and discarded, its spiritual energy depleted. Heye acquired 55 Yup´ik masks from the Kuskokwim River trader A. H. Twitchell in 1919. He later sold 35 of the masks to a group of surrealist artists, including Max Ernst and André Breton.

Respect for the animal world is also evident in Heye’s Subarctic materials, some of which were assembled by Frank G. Speck, an anthropologist who collected objects from the Innu (Montagnais–Naskapi) of northeastern Labrador. Multiple pieces reflect hunters’ respect for the spirit of their prey, particularly caribou, an Innu mainstay. Designs on coats, leggings, and blankets, such as the one shown in this section, symbolize a desire to honor the spirit of the caribou, ensuring successful hunting.

Contemporary and Modern Art

Since its founding in 1989, the National Museum of the American Indian has augmented Heye’s collection with some 15,000 pieces of modern and contemporary Native art. The largest single addition to the museum’s contemporary holdings was the transfer, in 2000, of the collection amassed by the Indian Arts and Crafts Board (IACB). This New Deal–era agency was created within the U.S. Department of the Interior to benefit Native people by expanding the market for Indian-made art. The IACB collection consists of approximately 6,300 objects, including sculpture, paintings, pottery, beadwork, dolls, textiles, and jewelry.

New acquisitions by the museum encompass Native art made using traditional media, such as pottery, basketry, and beadwork, as well as multimedia pieces, metal sculpture, and other works reflecting a clear and strong engagement with contemporary art.