Sunka Luta (Red Dog, Oglala Lakota, ca. 1848–d.?), ledger book drawings

ca. 1884

Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota

Paper, leather, graphite, ink, colored pencil

20 x 14 cm

Presented by Eleanor Sherman Fitch

20/6230

for similar objects.

“I have but few words to say to you, my friends. When the good spirit raised us, he raised us with good men for counsels and he raised you with good men for counsels. But yours are all the time getting bad, while ours remain good… When the Great Father (the President) first sent out men to our people, I was poor and thin; now I am large and stout and fat. It is because so many liars have been sent out there, and I have been stuffed full with their lies.”

—Red Dog, June 16, 1870

Red Dog, an itancan (leader) of the Oglala Oyuhpe band, lived during a time of great transition, when many Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota people first witnessed the arrival of non-Indians. He was the brother-in-law of the well-known Chief Red Cloud and by many accounts was called upon by Red Cloud to be his spokesman.

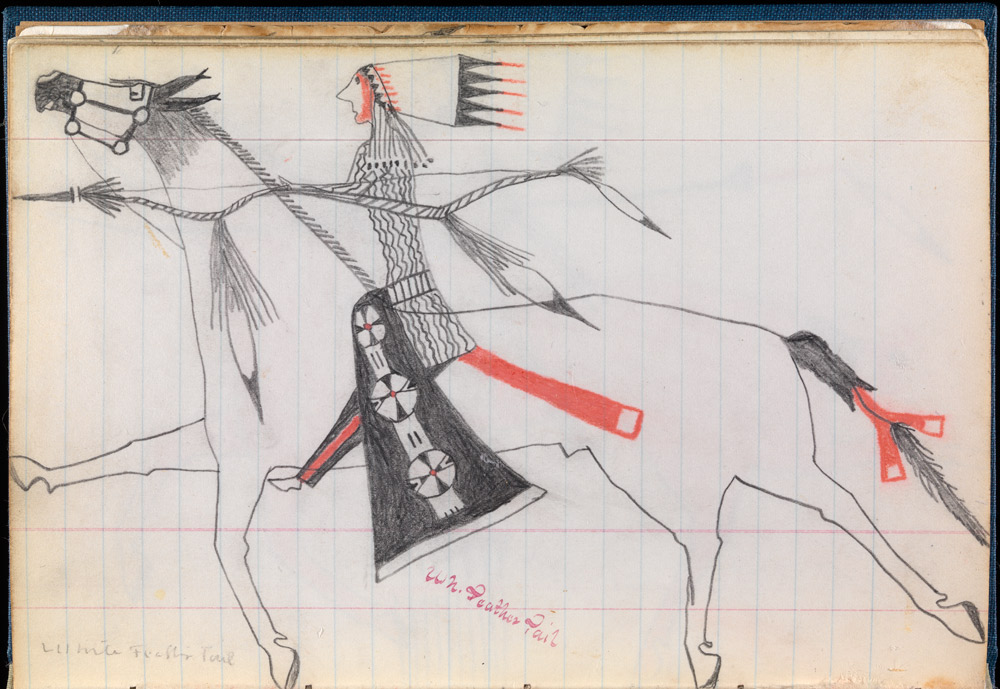

Around 1884 Red Dog created fifty-two crayon drawings. Similar pictographs in rock art most often recount events of war against an enemy or horse raiding against other tribes. Lakota men also painted their exploits in this manner on their tipi dwellings.

The drawings of White Tail and White Feather Tail show warriors dressed in fine Lakota regalia complete with headdresses, one horse’s tail tied up to prepare for action. Drawings often show a favorite spear, bow and arrows, rifle, or handgun, or maybe just a rope or coup stick. A rope would find its way around a loose horse, and a coup stick would be used to touch the enemy. It was more honorable to touch the enemy and get away with his possessions than to kill him. In Lakota values, being a warrior is an important aspect of bravery. Entering an enemy camp to take a prized horse or perhaps a herd of horses, often at high risk, was also a skillful act of bravery and chance. One eagle feather could be presented to a warrior for an outstanding deed. The riders in these drawings proudly display feathers they earned from previous encounters with the enemy.

—Donovin Sprague (Minnicoujou Lakota)

Historian and instructor, Black Hills State University